Artists have long translated the idiosyncrasies of perception into the language of art. Migraine auras, cataracts, and macular degeneration have been a driving force behind some of the world’s most influential works of art.

In this column, we’ll examine a handful of artists whose changing vision shaped how they represented both their inner experience and the physical world. Their perceptual disturbances influenced their technique, showing how art can make internal experience visible and invite viewers to inhabit another way of seeing.

Neurological Visual Disturbances

Giorgio de Chirico’s metaphysical paintings, such as The Mystery and Melancholy of a Street (1914), are defined by elongated shadows, skewed perspectives, and eerily empty urban landscapes. Scholars have suggested that some of these visual strategies mirror de Chirico’s experiences of migraine auras or temporal lobe epilepsy. De Chirico’s canvases do not depict these phenomena literally; instead, they function as a non-verbal translation of perceptual experiences, and the emotions that accompany them, through mysticism and symbolism.

Similarly, Sarah Raphael’s Strip series demonstrates how neurological visual disturbances can be transformed into structured abstraction. Composed of comic-like panels filled with geometric shapes and vibrant colors, these works were directly inspired by her experiences of migraine-related phosphenes. Raphael’s Strip series lays bare her internal world as she navigated debilitating migraine pain, visual disturbances, and addiction.

Ocular Disease and Age-Related Changes

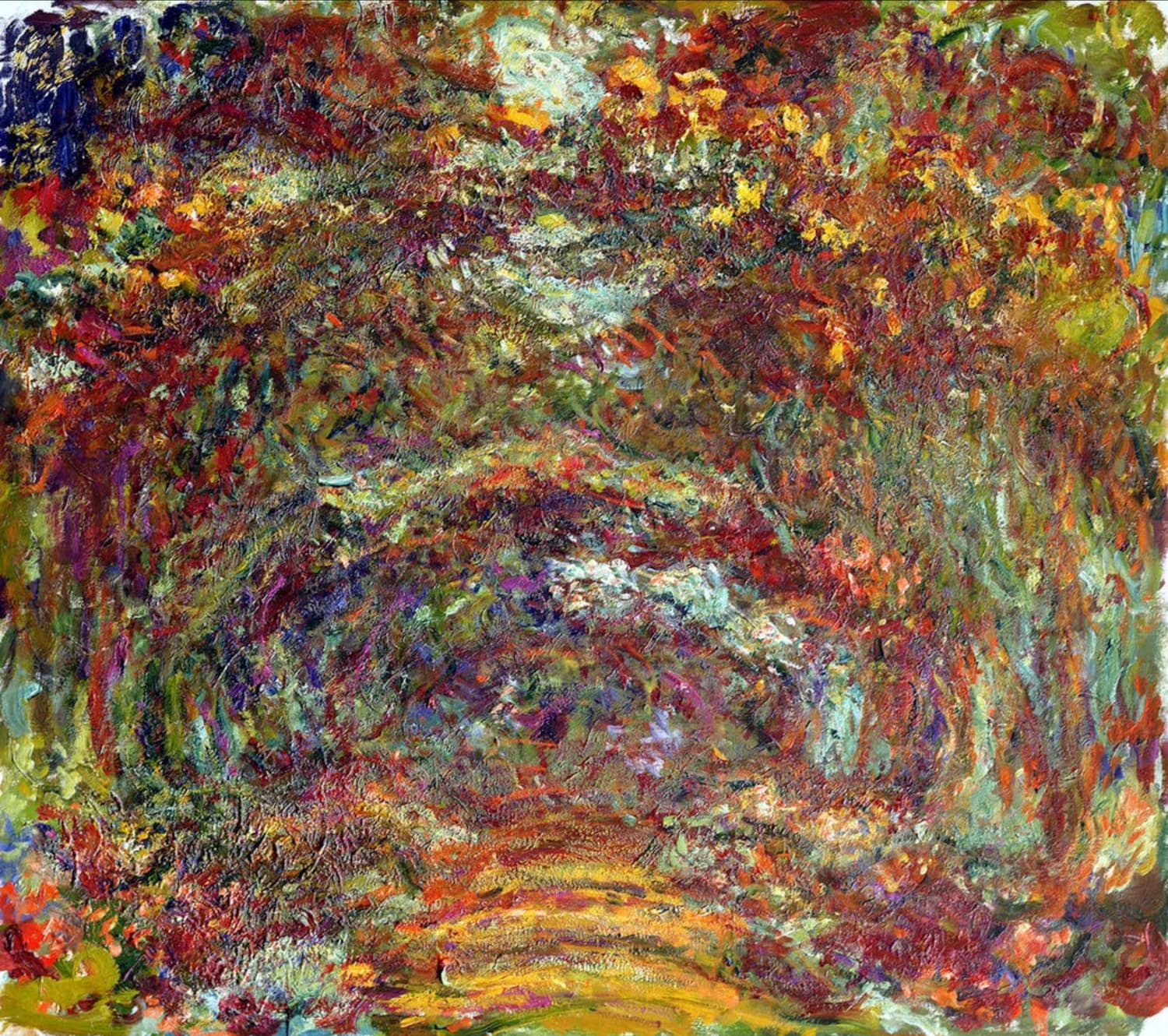

Artists have also adapted to chronic changes in ocular function, often turning limitation into stylistic innovation. Claude Monet’s later works, painted while he suffered from cataracts, show a shift toward warmer, hazier tones as seen in Path under the Rose Arches (1918-1924). Edges blur, colors favor yellows and reds, and the overall atmosphere softens. Monet’s evolving palette reflects the lived experience of cataracts and the personal adaptations required to keep painting.

Edgar Degas experienced progressive retinal degeneration, which gradually blurred his vision. In later works such as Woman Drying Her Hair (1905), he increasingly relied on broad strokes and pastels to compensate for vision changes. These adaptations allowed him to continue exploring form and movement while preserving expressive clarity. Degas’ stylistic evolution is often linked to the progression of his illness, with art historians observing measurable changes in refinement and detail as his vision deteriorated. His later works can thus be read as evidence of how his perceptual experience and artistic strategies adapted in response.

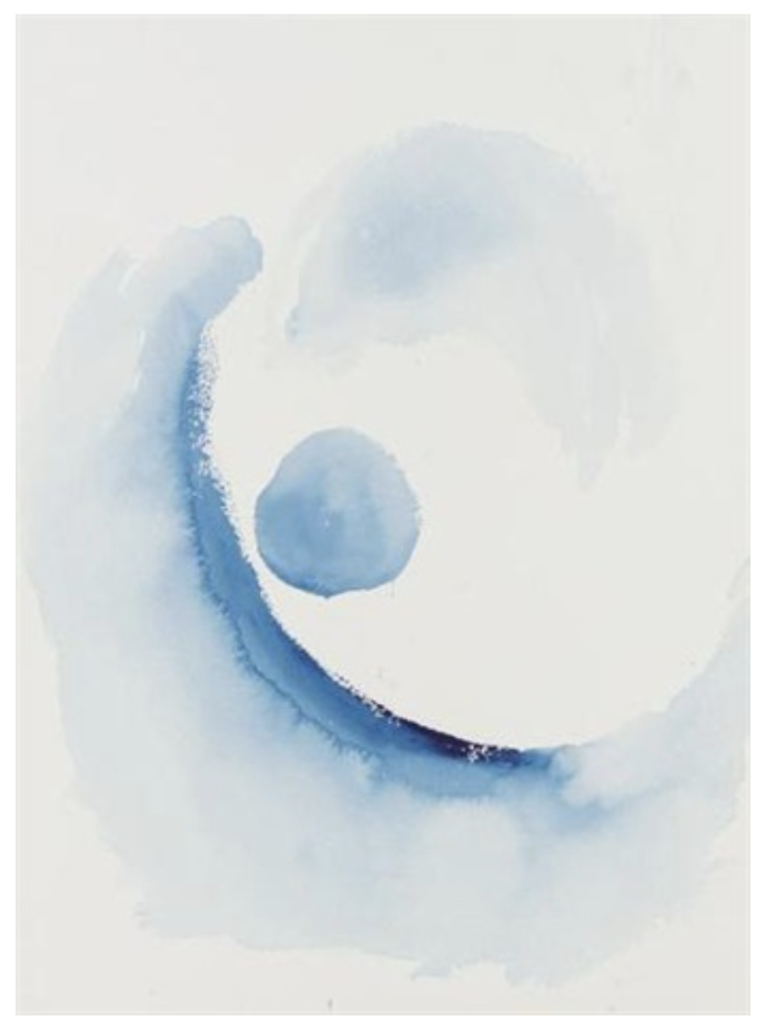

Georgia O’Keeffe contended with macular degeneration in later life, describing a persistent “cloud” in her central vision. In paintings such as Like an Early Blue Abstraction (1976-1977) O’Keeffe’s work shifts toward simplified forms and an emphasis on essential shape, with compositional clarity taking precedence over detail. These changes reflect both a practical adaptation to altered vision and a deeper reorientation of how she perceived and organized the visual world. These later works show how sensory change can register internally in artistic priorities while remaining fully integrated into a coherent, expressive practice.

Across these examples, a pattern emerges: artists who adapted their techniques in response to acquired changes in vision. Monet’s warm, hazy tones, Degas’ reliance on broad strokes and pastels, and O’Keeffe’s simplified forms all reflect adjustments to evolving perception and their influence on expression. For artists like de Chirico and Raphael, visual disturbances became a medium for processing perception and experience; the skewed perspectives and dreamlike emptiness of de Chirico’s metaphysical symbols and Raphael’s bursts of color and form translate internal phenomena into a shared emotional experience. Through color, form, and distortion, these works allow us a rare glimpse into the artists’ perceptual worlds and in doing so, we are invited to reflect on our own ways of seeing.

.jpg)

%20(2560%20x%201076%20px).jpg)