When Motivation Becomes Misguidance

One of the most cringe-worthy posts on the internet is the triumphant: “I proved them wrong.”

Don’t get me wrong, that person has every right to celebrate a major accomplishment.

And these triumphant posts can help dismantle harmful misconceptions like “DO students can’t become dermatologists” or “Low-income students can’t get into medical school.” That’s not what I’m addressing here.

But as someone who did the impossible by switching from Family Medicine to Dermatology on my first attempt, I will be the first person to tell you why it’s important not to fall into the trap of gloating “I proved them wrong.”

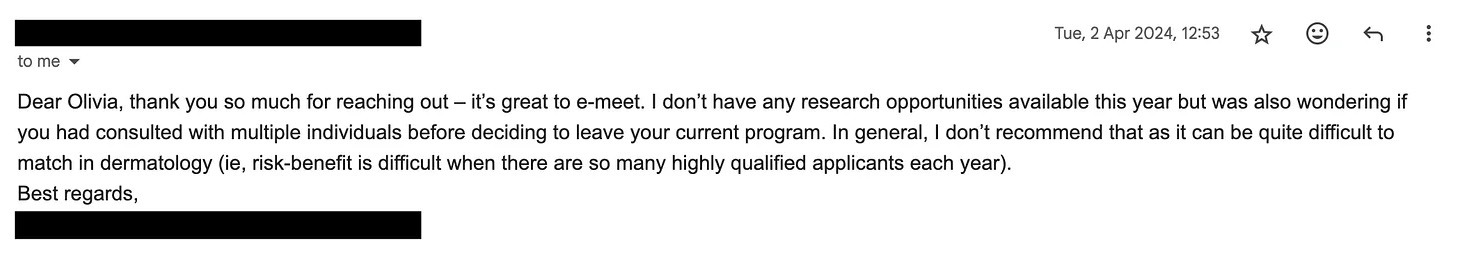

I received messages like these from mentors when I discussed my plans to switch residencies:

Beneath the victory lap in some of these “I proved them wrong” videos lies a deeper nuance worth unpacking: first, the trap of building your choices around “proving them wrong,” and second, the role of a good mentor: someone who tells it like it is and gives balanced guidance, even when the odds are steep.

I break this article into two parts and talk about:

- Why the “I proved them wrong” mindset can be a motivating but risky compass for career decisions.

- How a good mentor helps you sort out what’s truly possible, what’s risky, and what’s worth pursuing anyway.

First, An Important Nuance

Most “I proved them wrong” posts are framed in black-and-white terms:

1) your mentor advises you to do something

2) your mentor advises you not to do something

In my experience, the reality is usually more nuanced. Mentors tend to speak in shades of gray: “Have you thought about…?” “There are risks.” “I worry about your candidacy for these reasons...” “Have you considered a backup plan?”

Mentors are not universally advising, “don’t do it.” Their intent matters: many are cautioning you about risks, encouraging you to think through alternatives, and making sure you have a backup plan and not trying to shut down ambition.

Re-read this message from my attending, she is offering caution with nuance – not flat-out telling me what to do:

“I Proved Them Wrong” Is A Risky Compass

In medical careers, doubt and competition are constants. The urge to “prove them wrong” can be a powerful fuel. It pushes us through exams, applications, and setbacks. And I’m not saying we shouldn’t have these thoughts. In fact, some of the greatest innovations have probably been born from that very fire.

But if proving others wrong becomes your primary compass, it can steer you into the wrong specialty, program, or lifestyle.

Your competitive advantage will be learning to recognize this impulse, use it when it serves you, and rein it in when it doesn’t.

By becoming aware of these psychological defenses, you give yourself the freedom to decide: when to let ego drive, and when to take back the wheel in service of your long-term goals.

What’s Really at Play When We ‘Prove Someone Wrong’?

Ego & Identity Defense

- When someone says “you can’t do X” (X = get into med school, match a competitive specialty, land that fellowship), it feels like a threat to competence and identity.

- Choosing a path to “prove them wrong” reasserts self-worth.

Status & Prestige

- Competitive specialties and prestigious programs serve as visible proof of “winning.”

- It’s not just about the specialty or program itself, but about what it signals to peers, family, or doubters.

Narrative Reclamation

- There’s a storytelling impulse: “They said I couldn’t. And I did.”

- People love the redemption arc, and sometimes we chase it for the story rather than the fit.

Dopamine Reward Cycle

- Overcoming a doubter delivers a rush. But once achieved, the external motivation fades, leaving less satisfaction if intrinsic interest isn’t there.

Downsides in Career Selection

Mismatch Between Motivation & Fit

- Example: Choosing ENT or neurosurgery to prove your mentor wrong (or an ex, or that one bully from middle school) who said “you’re not cut out for a high-pressure specialty.”

- The short-term validation doesn’t sustain the day-to-day lifestyle, leading to dissatisfaction or burnout.

What Do I Actually Want?

When your career motivation revolves around proving others wrong, you unknowingly hand over control of your satisfaction to them. Every success becomes a rebuttal rather than a choice. And once you’ve silenced the critics, you’re often left facing a harder question: What do I actually want?

This mindset also comes with professional side effects. In medicine’s small world, being openly fueled by “I’ll show them” energy can be misread as defensiveness, competitiveness, or insecurity. Colleagues might interpret your decisions as ego-driven rather than rooted in curiosity, purpose, or patient care. Over time, that perception can subtly erode the authenticity of your professional relationships.

Perhaps the most damaging consequence, though, is internal. The drive to prove others wrong can be so loud that it drowns out quieter but more important questions: What kind of work actually energizes me? What values do I want my career to reflect? When your focus narrows to external validation, it delays the moment of self-awareness that real fulfillment requires.

By the time many people stop to ask those questions, they’ve already spent years walking a path designed to satisfy someone else’s expectations rather than their own.

Even Rejecting External Validation Can Still Mean Being Controlled by It

In some ways, I overcorrected by trying so hard not to “prove them wrong.” In medical school, I used to roll my eyes whenever stereotypes about dermatology came up. I didn’t see myself in any of them, and I didn’t want others to either. Looking back, I realize part of why I applied to Family Medicine instead of Dermatology was rooted in that resistance [Link to How I Changed Specialties series]. I didn’t want to be perceived as superficial, prestige-driven, or chasing an “easy lifestyle.” But avoiding a specialty because of how others might judge it is just as misguided as choosing one to prove them wrong. Either way, the decision is still about other people’s opinions, not your own values.

Everyone’s journey through medicine looks different. The best thing you can do for yourself is to stay self-aware, make choices that align with your own values, and celebrate others for doing the same.

Up next in Part 2: how a good mentor can help you avoid the trap of proving others wrong, provide perspective, highlight risks, and guide you toward decisions that truly align with your values.

%20(1).jpg)

%20(2560%20x%201076%20px).jpg)

%20(2560%20x%201076%20px).jpg)